Southeastern Mud Turtle

Kinosternon subrubrum subrubrum

Common Name: |

Southeastern Mud Turtle |

Scientific Name: |

Kinosternon subrubrum subrubrum |

Etymology: |

|

Genus: |

Kinosternon is derived from the Greek word kineo which means "move" and sternon which means "chest". This refers to the hinged plastron. |

Species: |

subrubrum is derived from the Latin word sub meaning "below" and ruber meaning "red". This refers to the reddish plastron color of hatchlings. |

Subspecies: |

subrubrum is derived from the Latin word sub meaning "below" and ruber meaning "red". This refers to the reddish plastron color of hatchlings. |

Average Length: |

2.8 - 4 in. (7 - 10 cm) |

Virginia Record Length: |

4.8 in. (12.3 cm) |

Record length: |

4.9 in. (12.4 cm) |

Systematics: Described originally as Testudo Subrubra by Pierre Joseph Bonnatere in 1789, who designated no type specimen or type locality. Schmidt (1953) restricted the type locality to the "vicinity of Philadelphia [Pennsylvania]." The genus Kinosternon was first used for this species by Bell (1825), referring to it as K. pennsylvanicum. This name was used by several authors in the Virginia literature (Hay, 1902; Dunn, 1915a; Wetmore and Harper, 1917), but subsequent authors followed Stejneger and Barbour (1917), who recognized only K. subrubrum. There are three recognized subspecies: K. s. subrubrum (Bonnatere), K. s. hippocrepis (Gray), and K. s. steindachneri (Siebenrock). Iverson (1977a) and Conant and Collins (1991) illustrated the ranges of these races. Only the nominate subspecies occurs in Virginia. Iverson (1991, Herpetol. Monog. 5: 1–27) and Iverson et al. (2013, Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 69: 929–939) are the most recent reviewers of this genus.

Description: A small freshwater turtle reaching a maximum carapace length (CL) of 125 mm (4.9 inches) (Iverson, 1977a). In Virginia, known maximum CL is 123 mm, maximum plastron length (PL) is 108.5 mm, and maximum body mass is 263 g.

Morphology: Carapace oval, generally smooth without overlapping scales, and sometimes flattened dorsally; weak middorsal keel may be present in some individuals; marginals 11/11, a single small cervical, pleurals 4/4, and vertebrals 5; 1st vertebral triangular and does not contact 2d marginal; height of 10th marginal usually twice that of others; bridge consists only of axillary and inguinal scutes; plastron 82-94% of CL; pectoral scute triangular in shape; width of posterior plastral lobe >50% carapace width; 2 plastral hinges allow considerable movement of anterior and posterior lobes; 11 plastral scutes, including a single triangular gular scute; median notch at posterior end of plastron usually present. The lower jaw usually has a sharply curved beak.

Coloration and Pattern: Carapace brown, olive, yellowish, or black, and usually patternless; ventral surface of marginals yellowish to brown; bridge brown; plastron brown or yellow with black or brown smudges; skin brown to gray, but sometimes black; limbs usually unpatterned; yellowish to white markings on head highly variable usually mottling on sides and dorsum but also may form an irregular stripe that does not extend to tip of snout; tomial surfaces of upper and lower jaws yellow to black.

Sexual Dimorphism: Adult males averaged 93.7 ± 7.2 mm CL (78.2-108.5, n = 100), 82.2 ± 7.3 mm PL (63.8-101.9, n = 100), and 157.3 ± 29.8 gbody mass (88-206, n = 93). Adult females averaged 92.8 ± 8.4 mm CL (75.7-123.0, n = 98), 84.8 ± 10.9 mm PL (65.5-107.8, n = 98), and 164.7 ± 32.0 g body mass (100-263, n = 87). Sexual dimorphism index was -0.01. Males have larger heads, deeper posterior plastral notches, longer tails with the cloacal opening extending beyond the posterior margin of the carapace (precloacal distance was 8-15 mm, ave. = 11.6 ± 1.9, n = 20), and a patch of raised scales behind the knee and thigh. Females have short tails with the anal opening at or near the tail base (precloacal distance was 0-5 mm, ave. = 1.2 ± 1.7, n = 17) and lack the patches of raised scales. Both sexes have spine-tipped tails.

Juveniles: The carapace of hatchlings has 3 indistinct keels, and it and the skin are black. Each marginal has an orange spot. The plastron is reddish with an irregular black figure that may cover nearly the entire surface or be narrow with black lines along the plastral seams. The black head has light stripes or is mottled. The snout is blunt. Hatchlings were 21.1-24.1 mm CL (ave. = 22.6 ± 0.8, n = 27) and 17.0-20.0 mm PL (ave. = 19.0 ± 0.8, n = 27), and weighed 2.3-3.4 g (ave. = 2.8 ± 0.3, n = 24).

Confusing Species: Sternotherus odoratus has a smaller plastron with a variable amount of white skin exposed between the scutes, a squarish pectoral scute, and a posterior plastral lobe width of <50% of carapace width. Hatchling stinkpots have black and yellow (or white) plastrons and pointed snouts. Kinosternon baurii in Virginia usually has 2 distinct yellowish stripes on each side of the head that extend to the tip of the snout, and sometimes 3 light carapacial stripes.

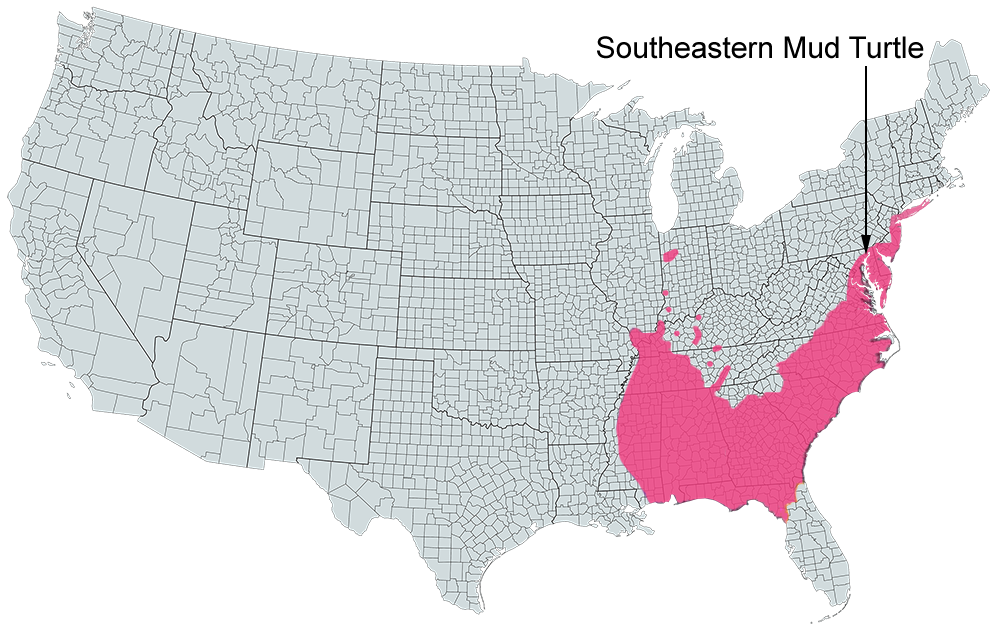

Geographic Variation: There is no discernible geographic variation in body size and scutellation in Virginia. A study of geographic variation throughout the entire range of K. subrubrum has not been published. The three subspecies (and K. baurii as currently recognized) differ in size of the plastron, percentage occurrence of stripes on the head, relative length of the interabdominal seam, and shape of the nasal scale (Ernst et al., 1974; Iverson, 1977a).

Biology: Kinosternon subrubrum occupies a wide variety of aquatic habitats, including ponds, lakes, creeks, swamps, freshwater and brackish marshes, ditches, and boggy areas. They avoid large, deep bodies of water and fast-moving water. Preferred habitat is shallow, slow-moving water, with aquatic or emergent vegetation and a soft organic substrate. This turtle is often seen on land, especially after rainstorms. Mud Turtles may spend a considerable portion of the year on land and often overwinter in shallow burrows (Gibbons, 1983). Wetmore and Harper (1917) found a mud turtle on 25 March near Alexandria, Virginia, that overwintered in a burrow 24 cm deep in a greenbrier (Smilax spp.) thicket. A mud paste encased the turtle at the bottom and, due to some dehydration of its skin, it was able to completely enclose its body in its shell (it was unable to do so after rehydration). Some individuals overwinter underwater in soft substrate or muskrat burrows. The usual activity season in Virginia is March to November, but individuals may be active on warm days in winter months.

Southeastern Mud Turtles are omnivores. Crayfish parts and seeds of water-lily (Nymphaea odorata) and black gum (Nyssa sylvatica) have been found in Virginia specimens. Mahmoud (1968) recorded insects, crustaceans, mollusks, amphibians, carrion, and aquatic vegetation for mud turtles from Mississippi. Ernst and Barbour (1972) noted that small Mud Turtles, <50 mm CL, prey on small aquatic insects, algae, and carrion, whereas larger ones feed on any type of food. Known predators of adults are raccoons (Procyon lotor), crows (Corvus spp.), eagles (Haliaeetus leucocephalus), and humans (Wetmore and Harper, 1917; Clark, 1982). Juveniles are eaten by large fish, Hog-nosed Snakes (Heterodon platirhinos), Nothern Cottonmouths (Agkistrodon piscivorus), and crows (Ernst and Barbour, 1972). Eggs are eaten by raccoons, skunks (Mephitis), weasels (Mustek spp.), opossums (Didelphis virginiana), and Eastern Kingsnakes (Lampropeltis getula) (Richmond, 1945b; Ernst and Barbour, 1972; Knight and Loraine, 1986).

Mating occurs mid-March to May (Ernst and Barbour, 1972). I observed mating in Henrico County on 4 April 1982. Courtship and mating behavior is similar to that described in the Sternotherus odoratus account. Nesting has been observed between 31 March and 22 June (Richmond, 1945b; Gotte, 1988). I recorded oviductal eggs in females between 19 March and 8 June. Richmond (1945b) described nest construction as follows: (1) the female tries several sites before, selecting a suitable one; (2) she digs first with the forefeet-thrusting dirt outward laterally-until she is concealed; (3) she then turns around and completes the nest with the hind feet, remains in the cavity for egg laying with only the head visible, and covers the eggs in the cavity with soil; and finally (4) she levels and scratches around the site but makes only a slight effort to conceal the nest. A nest Richmond recorded was 7.6-12.7 cm deep at a 30° angle. Most nesting occurs during or after rain- storms (Richmond, 1945b; Gotte, 1988). Females often deposit their eggs under decaying vegetation, under boards, and on open ground (Ernst and Barbour, 1972; Gotte, 1988). Size at maturity was measured to be between 70 and 80 mm CL (Gibbons, 1983). In Virginia, female Mud Turtles lay one, two, or more clutches per season. Gibbons (1983) reported up to four clutches are produced by South Carolina females. Clutch size in Virginia was 2-5 eggs (ave. = 3.5 ± 1.1, n = 13), compared with 1-8 (ave. = 2.6 ± 1.0) from throughout its range (Gibbons, 1983) and 1-6 (ave. = 3.2 ± 1.0) in a South Carolina population (Frazer et al., 1991). Richmond (1945b) reported clutch sizes of 2-5 eggs (ave. = 3.4) found in 14 nests in New Kent County, and C. H. Ernst (pers. comm.) recorded 2-4 eggs (ave. = 3.0) in six nests found in Fairfax and Prince William counties. Eggs in Virginia populations averaged 26.0 ± 1.6 x 16.1 ±1.0 mm in size (length 25.1-29.0, width 13.8-18.2, n = 30) and 4.2. ± 0.7 g in mass (3.3- 5.8, n = 29). Laboratory incubation time was 87- 104 days (ave. = 92,4 ± 5.8, n = 8) and hatching occurred between 23 August and 16 October. Hatchlings in South Carolina overwinter in the nest and emerge primarily March to May (Gibbons, 1983). Five hatchlings were found in three nests plowed up on 1 April 1942 in New Kent County (N. D. Richmond, pers. comm.). There is some indication that eggs laid in the fall do not begin embryonic development until spring (= embryonic diapause), as eggs collected and preserved on 26 December 1952-3 January 1953 from New Kent County had not started visible development. However, not all eggs or hatchlings overwinter, as wild-caught hatchlings have been found on 23 August and 8 October.

The population ecology of K. subrubrum has not been studied in Virginia. Mud Turtles are abundant in swamps and shallow ponds in southeastern Virginia but uncommon in Piedmont lakes. In South Carolina, Gibbons (1983) estimated that there were 224-556 Mud Turtles in a 10-hectare Carolina bay over a 10-year period and that substantial emigration out of the pond to terrestrial burrows occurred during drought. Gibbons (1983, 1987) also reported that growth rates of adults was <1.0 mm per year and the natural life span may be in excess of 30 years. Frazer et al. (1991) determined that survivorship of adult females (87.6%), adult males (89.0%), and hatch- lings (26.1%) in a South Carolina population was higher than that for sympatric Trachemys scripta, and that a higher percentage of the female population was reproductively active each year.

Southeastern Mud Turtles are bottom walkers, spending most of their active time in water on the bottom. A substantial but unknown portion of their annual activity period is terrestrial. They seldom bask. Southeastern mud turtles are pugnacious when caught and many will try to bite, causing a minor wound from the curved beak.

Remarks: Other common names in Virginia are "box terrapins" (former inhabitants of Hog Island, Northampton Co.; Brady, 1925), common mud turtle (e.g., Conant, 1945; Hoffman, 1949b; Carroll, 1950), and skillpot (Hay, 1902).

Mitchell and McAvoy (1990) sampled six individuals in natural populations in Virginia for pathogenic Salmonella bacteria. None was found. The systematic relationship between Kinosternon subrubrum and K. baurii needs to be explored, as it is often difficult to separate the two species morphologically. The sample used in the description here was derived from specimens outside of the areas known to contain putative K. baurii populations. Additional comments are in the K. baurii account.

Conservation and Management: This species appears to be secure in Virginia, but loss of wetland habitats could jeopardize local populations. Information on population sizes, the demography of selected populations in different habitats, and terrestrial movement ecology is necessary to identify the sensitive phases in its life history. Active management must include maintenance of shallow wetlands, including swamps and Carolina bays, and the associated terrestrial habitat. A terrestrial buffer zone around aquatic habitats of at least 150 m is needed to ensure the survival of local populations (V. J. Burke, pers. comm.).

References for Life History

Photos:

*Click on a thumbnail for a larger version.

Verified County/City Occurrence in Virginia

Accomack

Amelia

Appomattox

Arlington

Brunswick

Buckingham

Campbell

Caroline

Charles City

Charlotte

Chesterfield

Cumberland

Essex

Fairfax

Gloucester

Goochland

Greensville

Halifax

Hanover

Henrico

Isle of Wight

James City

King and Queen

King George

King William

Louisa

Mathews

Mecklenburg

Middlesex

New Kent

Northampton

Northumberland

Nottoway

Orange

Pittsylvania

Powhatan

Prince Edward

Prince George

Prince William

Richmond

Southampton

Stafford

Surry

Sussex

Westmoreland

York

CITIES

Alexandria

Chesapeake

Danville

Hampton

Newport News

Poquoson

Richmond

Suffolk

Virginia Beach

Williamsburg

Verified in 46 counties and 10 cities.

U.S. Range

002_small.jpg)

_small.jpg)

001_small.jpg)

102_small.jpg)