Eastern Ratsnake

Pantherophis alleghaniensis

** Harmless **

Common Name: |

Eastern Ratsnake |

Scientific Name: |

Pantherophis alleghaniensis |

Etymology: |

|

Genus: |

Pantherophis from the Greek words panther, meaning "panther" and ophis, meaning "snake". |

Species: |

alleghaniensis refers to its habitat in the Allegheny Mountains. |

Vernacular Names: |

black ratsnake, Alleghany black snake, black chicken snake, black Coluber, black pilot snake, black racer, blue racer, chicken snake, mountain black snake, mountain pilot snake, pilot, racer, rat snake, rusty black snake, scaly black snake |

Average Length: |

42 - 72 in. (106.7-183 cm) |

Virginia Record Length: |

79.8 in. (202.8 cm) *Note: The eastern ratsnake is the only 6+ foot snake found in Virginia |

Record length: |

101 in. (256.5 cm) |

Systematics: Originally described as Coluber obsoletus by Thomas Say in 1823 from a specimen collected at "Isle au Vache to Council Bluffs on the Missouri River." Schmidt (1953) restricted the type locality to Council Bluffs, Iowa. Dunn (1915a) was the first to use the genus Elaphe for this species but spelled the species obsoletus. In 1836, Holbrook described Coluber alleghaniensis from a specimen found "on the summit of the Blue Ridge in Virginia." This specimen and others from New York and the Carolina mountains were the first Eastern Ratsnakes he saw that had weakly keeled scales. The name was later considered a junior synonym of E. obsoletus (= obsoleta) by Cope (1900). Callopeltis obsoletus was used for this species by Hay (1902), following Lonnberg (1894). Based on the congruence of morphological (Burbrink, 2001, Herpetol. Monogr. 15: 1–53) and mitochondrial data (Burbrink et al., 2000, Evolution 54: 2107–2118), Burbrink divided P. obsoletus into three species (P. alleghaniensis, P. obsoletus and P. spiloides) with no subspecies. P. alleghaniensis is the only species found in Virginia.

Description: A large, stout snake reaching a maximum known total length of 2,565 mm (101.0 inches) (Conant and Collins, 1991). In Virginia, maximum known snout-vent length (SVL) is 1,710 mm (67.3 in.) and maximum total length is 2,028 mm (79.8 in.). In this study, tail length/total length averaged 16.9 ± 1.6% (11.2-23.6, n = 209).

Scutellation: Ventrals 214-272 (ave. = 231.8 ± 5.2, n = 232); subcaudals 46-94 (ave. = 80.0 ± 7.4, n = 203); ventrals + subcaudals 275-348 (ave. = 312.1 ± 9.3, n = 201); dorsal scales smooth laterally and weakly keeled middorsally, scale rows usually 24-27 (77.1%, n = 251) at midbody, but may be 21-23 or 28 (22.9%); anal plate undivided (10.8%) or divided or partially divided (89.2%, n = 232); infralabials 11/11 (47.3%, n = 167), 10/10 or 10/11 (21.6%), 11/12 or 12/12 (21.6%), or other combinations of 9-13 (9.5%); supralabials 8/8 (89.3%, n = 224) or other combinations of 6-9 (10.7%); loreal present; preoculars 1/1; postoculars 2/2; temporals usually 2+3/2+3 (52.4%, n = 229), 2+2/2+3 (13.1%), 2+2/2+2 (10.5%), 2+4/ 2+3 (10.0%), or other combinations of 1-3/2-6 (14./4%).

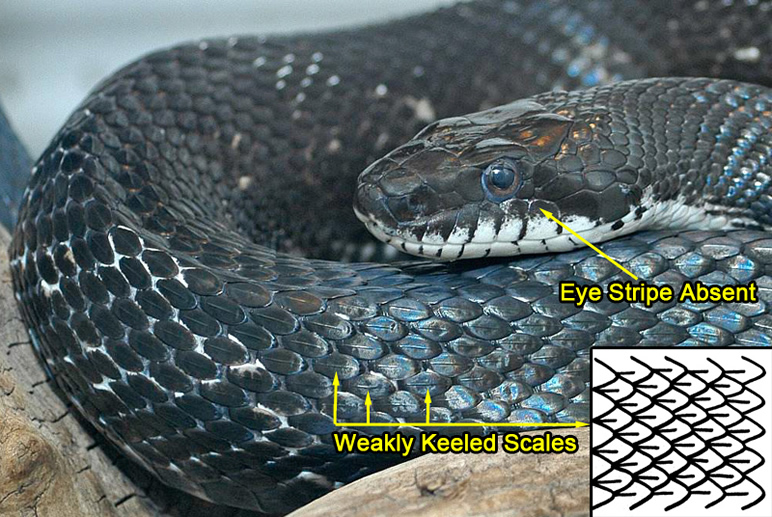

Coloration and Pattern: Body uniformly black dorsally in adults; some individuals with faint black stripes on a gray-black body or with juvenile pattern incompletely obscured (see below); venter with an irregular black-and-white checker-board pattern interspersed with black smudges, with pink replacing white in some individuals; ventral pattern fades posteriorly becoming all gray in older adults but a black-and-white pepper pattern in younger individuals; chin and anterior portion of venter of neck plain white; white pigment also occurs on lower half of supralabials. The body in imaginary cross section is shaped like a bread loaf, with a flat venter.

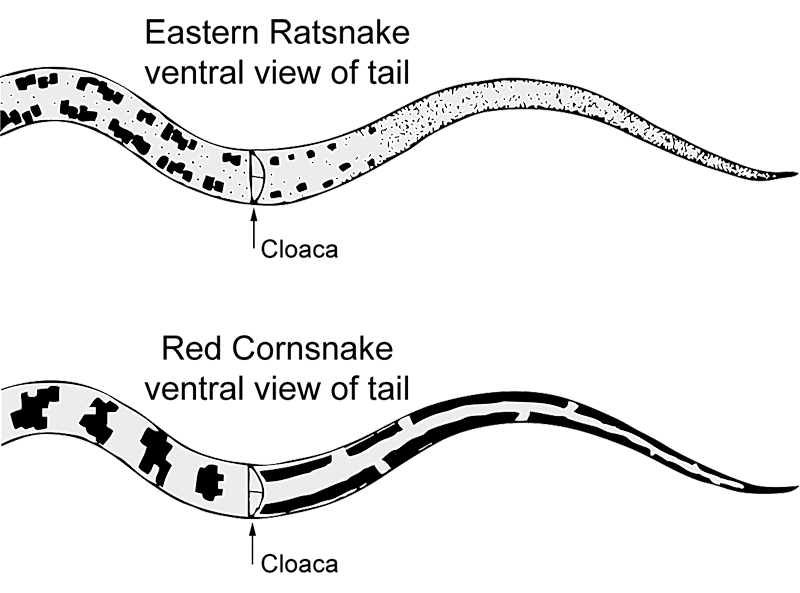

Sexual Dimorphism: There are no sexual differences in color or pattern. Adult male SVL (908-1,710, ave. = 1,182.1 ± 187.1, n = 124) was similar to adult female SVL (910-1,590, ave. = 1,136.1 ± 156.0, n = 54). Sexual dimorphism index was -0.04. Males attained longer total lengths (to 2,028 mm) than females (to 1,884 mm). Tail length relative to total length was higher in males (ave. = 17.5 ± 1.4%, 15.1-23.6, n = 107) than in females (ave. = 15.7 ± 1.3%, 11.2-18.0, n = 47). Average ventral scale counts were slightly higher in females (233.4 ± 7.3, 214-272, n = 50) than in males (230.7 ± 3.9, 220-246, n = 112). The average number of subcaudal scales was higher in males (82.5 ± 5.7, 64-94, n = 96) than in females (74.3 ± 8.6, 46-88, n = 45), but the average number of ventrals + subcaudals was similar between sexes (males 313.3 ± 7.6, 290-337, n = 95; females 308.4 ± 11.5, 275-348, n = 44).

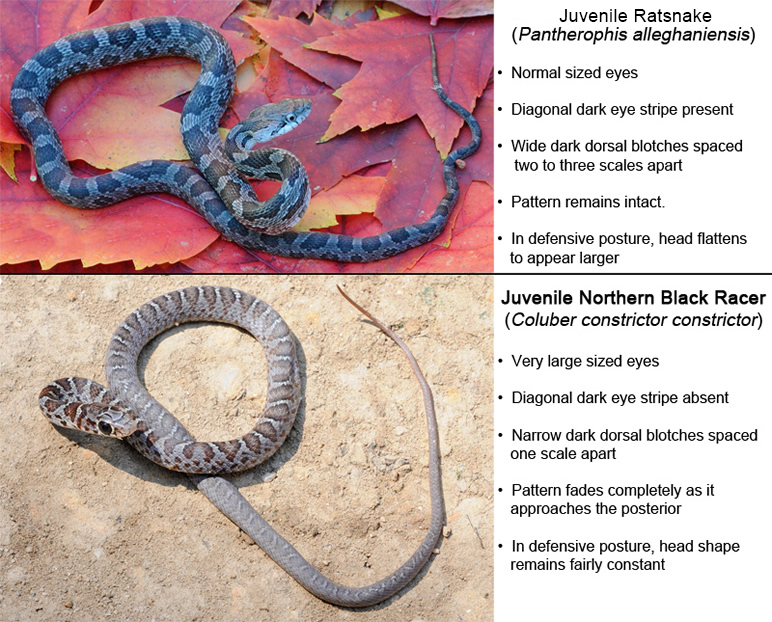

Juveniles: In contrast to adults, juveniles exhibit a strong pattern of black to dark-brown blotches dorsally (ave. = 33.5 ± 2.9, 28-40, n = 36) on a peppered black-and-white to gray body. The anterior blotches have anterior and posterior projections on the corners. The brown and white venter forms a checkerboard pattern. There is a distinct brown stripe that starts in front of the eye and runs to the margin of the mouth. These are connected by a brown band across the dorsum of the head. The venter of the tail has an irregular dark stripe along each side. The juvenile pattern is usually obscured at a SVL of about 650 mm. Some young adults may exhibit a faint dorsal blotch pattern, which also may be seen in full-grown adults in some areas (see "Geographic Variation"). At hatching, juveniles in Virginia averaged 284.6 ± 14.2 mm SVL (258-318, n = 48) and 343.9 ± 17.3 mm total length (317-391, n = 47), and weighed 9.4-13.2 g (ave. = 11.7 ± 1.2, n = 21).

Confusing Species: Adult Eastern Ratsnakes may be confused with adult Coluber constrictor; however, the latter has entirely smooth scales and a round body in cross section, and the white pigment is confined to the chin. Juvenile C. constrictor lack the eye-jaw stripe, the checkerboard pattern on the venter, the projections on the anterior dorsal blotches, and the stripes on the venter of the tail. They also possess 1.5-2 times the number of dorsal blotches. Juveniles are sometimes confused with small Agkistrodon contortrix, but Eastern Copperheads have brown hourglass-shaped crossbands and a yellow tail tip.

Geographic Variation: Adult Pantherophis alleghaniensis are uniformly black dorsally throughout most of Virginia. Individuals from the extreme southeastern corner and in the vicinity of Greensville County show varying traces of the four longitudinal black stripes on a dark-gray background. Some individuals in southwestern Virginia, particularly in Pulaski and Washington counties, retain some of the juvenile pattern, but the variation is great. The average number of ventral scales did not vary significantly among physiographic regions, ranging from 229.3 ± 4.8 (220-237, n = 12) on the Eastern Shore to 233.9 ± 3.4 (230-243, n = 13) in the lower Piedmont. The average number of subcaudal scales was lowest in populations southwest of the New River in the Ridge and Valley region (74.9 ± 9.6, 54-82, n = 14) and highest (82.8 ± 6.1, 60-92, n = 35) in the northern Piedmont. Average number of ventrals + subcaudals followed a similar pattern (SW Ridge and Valley 306.8 ± 11.3, 286-318, n = 14; N Piedmont 315.6 ± 6.9, 296-328, n = 35).

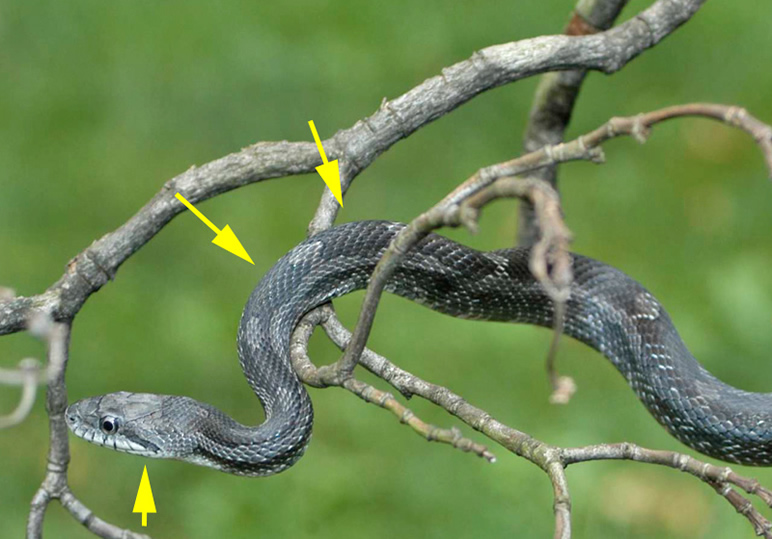

Biology: Eastern Ratsnakes are the most commonly seen snakes in Virginia. They are terrestrial and arboreal. They occur in many types of habitats, including agricultural areas, most types of hardwood forests, isolated urban woodlots, and forested wetlands. These snakes are often found in barns and old buildings where their primary prey, small rodents, occur in abundance. Hutchison (1956) found one in the mouth of a cave. Eastern Ratsnakes are diurnal and nocturnal. They are often active just after sunset. During this time they move considerable distances and many are killed by vehicles on roads. This species experiences great losses each year due to this source of mortality. Museum records for Virginia P. alleghaniensis indicate an activity period of 3 April-8 December. Brief activity is known to occur in winter months but depends on weather conditions. Clifford (1976) found them active May-September in Amelia County, and Bazuin (1983) noted an activity season of 11 March to 8 November in Louisa County. Body temperatures of active snakes were 25.0-30.6°C (ave. = 27.6 ± 1.9, n = 11). Snakes found undercover objects were 15.0-18.9°C (ave. = 17.5 ± 2.2, n = 3).

Rodents, birds, and birds' eggs are the preferred prey of P. alleghaniensis. The following species have been recorded (Uhler et al., 1939; this study): mammals-eastern chipmunks (Tamias striatus), gray squirrels (Sciurus carolinensis), eastern cottontails (Sylvilagus floridanus), southern flying squirrels (Glaucomys volans), meadow voles (Microtus pennsylvanicus), pine voles (Microtus pinetorum), white-footed mice (Peromyscus leucopus), and northern short-tailed shrews (Blarina brevicauda); birds-American robins (Turdus migratorius), eastern bluebirds and eggs (Sialia sialis), yellow-bellied sapsuckers (Sphyrapicus varius), downy woodpeckers (Picoides pubescens), gray catbirds (Dumetella carolinensis), brown thrashers (Toxostoma rufum), eastern meadowlarks (Sturnella magna), song sparrows (Melospiza melodia), ruby throated hummingbirds (Archilochus colubris), waterthrushes (Seiurus noveboracensis), an unidentified warbler, a "blackbird," and grouse or quail eggs; reptiles: Five-lined Skinks (Plestiodon fasciatus) and unidentified snakes and snake eggs; amphibians: Lithobates spp. The snake eating the brown thrasher had consumed a parent and a nestling. Many of the birds taken were nestlings. Other prey recorded for Virginia snakes are Eastern Fence Lizards (Sceloporus undulatus) (Richmond and Goin, 1938) and bank swallows (Riparia riparia) Blem, 1979). Additional prey types for this species were listed in Brown (1979) and Ernst and Barbour (1989b). There are numerous observations of P. alleghaniensis climbing trees to prey upon birds and their eggs and nestlings. These snakes are occasionally seen eating domestic chicken eggs and sometimes objects that look like them. Once caught, prey are killed by constriction, although eggs are swallowed and then broken in the throat. Individuals of P. alleghaniensis, which hunt by olfaction and vision, were shown in a study in Warren County to consume more territorial male and lactating female meadow voles (Microtus pennsylvanicus) than nonlactating females because of the increased defensive behavior of those groups (Madison, 1978). Predators of P. alleghaniensis include hawks (Buteo spp.), great homed owls (Bubo virginianus), and free-ranging domestic cats (Mitchell and Beck, 1992; C. H. Ernst, pers. comm.).

Eastern Ratsnakes are oviparous and lay one clutch of 5-19 eggs per year (ave. = 11.3 ± 3.3, n = 24). Clutches from 21 northern Virginia P. alleghaniensis averaged 19.4 eggs (17-24; C. H. Ernst, pers. comm.). Natural egg-laying sites include standing and fallen hollow trees, compost and mulch heaps, sawdust piles, and decomposing logs. Some sites are used repeatedly by P. alleghaniensis (Bader, 1984). Male combat sometimes precedes mating (Mitchell, 1981b). Known mating dates are between 26 May and 9 June. Recorded egg-laying dates are 3 June-17 July (Tuck et al., 1971; W. H. Martin, pers. comm.; C. A. Pague, pers. comm.; J. C. Mitchell, pers. obs.). Eggs averaged 42.8 ± 6.2 x 24.7 ± 4.3 mm (length 34.0-57.3, width 19.3-39.5, n = 61) and weighed 9.0-13.1 g (ave. = 11.6 ± 0.8, n = 26). All mature males and females I measured were over 900 mm in SVL. Length of incubation was 60-65 days, and hatchlings emerged 30 August-30 September.

This is the most commonly encountered snake in Virginia. Of 278 snakes recorded over a 4-year period in Amelia County, 105 were Eastern Ratsnakes (Clifford, 1976). In the Blue Ridge Mountains, Martin (1976) noted that 76 of 545 snakes he found on roads were this species. Shekel et al. (1980) found a density of 0.23 snake per hectare in Maryland, and Fitch (1963b) found 1 per hectare in Kansas. Adult Eastern Ratsnakes occupy a home range up to 600 m in diameter, and the same home ranges are occupied for many years and possibly life (Stickel et al., 1980). Maximum distances moved are over 1,300 m. These snakes usually use a cover site repeatedly during the active season and the same hibernaculum for years. The most common hibernacula are hollow trees and stumps. These usually harbored single snakes. Black rat snakes have been known to aggregate in winter, sometimes in the same dens in which Eastern Copperheads (Agkistrodon contortrix) hibernate. Such a site was discovered on 15 April 1967 in a pile of rotting timbers in Loudoun County by W. H. Martin (pers. comm.).

Remarks: Other common names in the Virginia literature are pilot snake (Cope, 1900), Alleghany blacksnake (Hay, 1902), scaly or rusty black snake and pilot snake (Dunn, 1915a), tree black snake (Dunn, 1936), mountain blacksnake (Burch, 1940), pilot blacksnake (Burch, 1940; Conant, 1945), and chicken snake (Linzey and Clifford, 1981).

The belief that Eastern Ratsnakes and Eastern Copperheads hybridize and produce offspring that are venomous and look like Eastern Ratsnakes is a myth. These two species are only distantly related (different families), indicating that compatible mating and production of viable offspring is highly unlikely. Other stories about black snakes (presumably Eastern Ratsnakes) are commonplace. Beck (1952) mentions several myths believed by people in Rappahannock County in 1948, including Eastern Ratsnakes being able to kill rattlesnakes with herbal weeds, stand on their tails, milk cows, and charm birds and children. The myth that Eastern Ratsnakes guide copperheads and rattlesnakes to safety may have resulted in the name "pilot" for this species (Ernst and Barbour, 1989b).

Albino or partial albino P. alleghaniensis specimens have been reported from three locations in Virginia: Westmoreland County (Hensley, 1959), Rockbridge County (Carroll, 1950), and Washington County (D. W. Ogle, pers. comm.). The latter two snakes retained the juvenile pattern but had no black pigment.

Mitchell et al. (1982) reported the unusual behavior of autophagy (self-consumption) in a juvenile P. alleghaniensis from Chesterfield County. The snake had been subjected to a sudden change in temperature, began biting its own tail, swallowed it completely (along with as much of the rest of the body as it could), and died. This resulted in three concentric coils, one outside and two inside, with a diameter of 4 cm.

Eastern Ratsnakes occasionally enter power transformers, become electrocuted, and cause power outages. One such incident left 13,000 homes without power in Chesterfield County (Richmond Times-Dispatch, 29 May 1991).

Conservation and Management: The abundance and widespread occurrence of this species and its ability to survive in a wide variety of habitats indicate that P. alleghaniensis currently needs little protection and active management. However, hundreds of individuals are killed on Virginia's highways each year, a source of mortality that public education about snakes might help to reduce. How this species responds to habitat fragmentation is unknown. Management for the continued presence of this species includes the maintenance of large stands of hardwood forests.

References for Life History

Neonates and juveniles are boldly patterned with 28-40 dark blotches on a gray background. A dark diagonal eye stripe extends from in front of the eye and runs to the margin of the mouth. The dorsal pattern remains discernible almost down to tail tip. The juvenile dorsal pattern usually fades to a solid black as the snake approaches 2 feet in total length. However, in some individuals a slight hint of the juvenile pattern may be retained for life. The juvenile eastern ratsnake pictured below is approximately 16 in. in total length.

The eastern ratsnake pictured below is 2 ft. in total length. While both dorsal pattern and eye stripe are fading, they are still discernible.

The specimen pictured below has reached 3 ft. in total length. The eye stripe and dorsal pattern are almost completely obscured.

The below 5 ft. specimen has a completely black dorsum.

Note the lack of eye stripe and the weakly keeled scales in the adult eastern ratsnake pictured below.

The venter (belly) of the eastern ratsnake is black and white, often resembling a checkerboard pattern with interspersed black blotches. This pattern fades as it approaches the posterior. In the cross-section the body shape of the eastern ratsnake is shaped similar to that of a loaf of bread.

Defensive Behaviors

As with all our native snakes the eastern ratsnake would rather flee than fight. However, if the snake feels cornered it will bite. In an effort to appear more formidable, the eastern ratsnake distort the shape and size of its head when threatened.

Another defensive strategy involves the ratsnake raising the front portion of its body off the ground in a 'S' shape coil. This makes the snake look more formidable and increases the snake's effective striking range. It's not uncommon for the snake to hiss loudly as it strikes from this position.

Confusing Species

The species most often mistaken for an eastern ratsnake in Virginia is the northern black racer.

Both the eastern ratsnake and the northern black racer have a juvenile pattern that does not resemble the adult version.

Unlike the eastern ratsnake which has weakly keeled scales, the scales of the northern black racer are smooth.

Both the eastern ratsnake and the northern black racer have a whitish chin and neck.

Unlike the checkerboard pattern found on the ventral side of the eastern ratsnake, the venter

of the northern black racer is a solid dark gray that changes to a light gray under the tail.

Photos:

*Click on a thumbnail for a larger version.

Verified County/City Occurrence in Virginia

Accomack

Albemarle

Alleghany

Amelia

Amherst

Appomattox

Arlington

Augusta

Bath

Bedford

Bland

Botetourt

Brunswick

Buchanan

Buckingham

Campbell

Caroline

Carroll

Charles City

Charlotte

Chesterfield

Clarke

Craig

Culpeper

Cumberland

Dinwiddie

Essex

Fairfax

Fauquier

Floyd

Fluvanna

Franklin

Frederick

Giles

Gloucester

Goochland

Grayson

Greene

Greensville

Halifax

Hanover

Henrico

Henry

Highland

Isle of Wight

James City

King and Queen

King George

King William

Lancaster

Lee

Loudoun

Louisa

Madison

Mathews

Mecklenburg

Middlesex

Montgomery

Nelson

New Kent

Northampton

Nottoway

Orange

Page

Patrick

Pittsylvania

Powhatan

Prince Edward

Prince George

Prince William

Pulaski

Rappahannock

Richmond

Roanoke

Rockbridge

Rockingham

Scott

Shenandoah

Smyth

Southampton

Spotsylvania

Stafford

Surry

Sussex

Tazewell

Warren

Washington

Westmoreland

Wise

Wythe

York

CITIES

Alexandria

Charlottesville

Chesapeake

Hampton

Lynchburg

Manassas

Martinsville

Newport News

Norfolk

Petersburg

Poquoson

Portsmouth

Radford

Richmond

Suffolk

Virginia Beach

Winchester

Verified in 91 counties and 17 cities.